Any decent

autobiography only begins with the story of the author’s life. Sure,

there are plenty of autobiographies that tell a decent story, but only in the

same way that Kipling or Stephenson can tell a decent story. If an

autobiography is going to be worth anything, it really has got to say something.

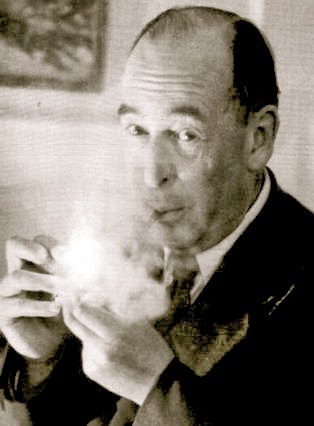

There are many

moment in C.S. Lewis’s autobiography, Surprised

by Joy, that have stuck with me since the first time I read it—moments

where, in the midst of a life’s story, something was being said, and that something represented a truth far beyond the truth

or falsehood of the events surrounding them.

At some point,

Lewis, remembering (though not particularly fondly) the many years at school during

which he would have considered himself a sound and stalwart humanist—I time

spent desperately seeking to avoid falling back into the bottomless pit of

belief—observed that, “A young man who wishes to remain a sound Atheist cannot

be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere—‘Bibles laid open,

millions of surprises,’ as Herbert says, ‘fine nets and stratagems.’ God is, if

I may say it, very unscrupulous.” Later, much along the same lines, he reminds

his reader that: “Really, a young Atheist cannot guard his faith too carefully.

Dangers lie in wait for him on every side.”

Now, Lewis

should understand the feelings of atheism significantly better than I, for he

experienced it, in all of inglory, from within, while the entire scope of my

knowledge comes from reading and observation. From without. I would not dare

complain, of course. While a Christian may, in fact, experience some tangible

benefit from having experienced part of his life as an atheist, he will also

have given up a perfectly good portion of time to endlessly futile pursuits. In

the same way, I think there is certainly an argument to be made for a few years

in prison as a character-building opportunity, but that doesn’t change the fact

that going there is generally a waste of one’s time.

So I do not plan

on embarking into an adventure in atheism any time soon (I am much too far gone

for that), though I am grateful for a man like Lewis, who ‘took the bullet’, as

it is said. He wasted years of his life so that I wouldn’t have to (comparisons

to Christ here may be warranted, but I can’t help but feel that Lewis would

disapprove, so I hold my tongue). He writes of time as an atheist like a spy

reporting from behind enemy lines (though, in his case, an unknowing spy).

I wrote

previously of Malcolm Muggeridge and G.K. Chesterton, each of whom experienced

their own conversions somewhat later in life, though with Lewis it is

different: He did not, as did Muggeridge and Chesterton, travel the short

distance between uncertainty (or agnosticism) and belief. Experiencing a very

nominal form of Christianity as a young man, which he quickly abandoned after

heading out on his own, he was forced to travel the almost unimaginable

difference between one firm, staunch, impenetrable belief (it would be a pity

to call atheism a “lack of belief”) and another. The two might as well have

stood on opposite sides of the universe. He is not the only Christian to have traversed

this gulf, of course, though he is perhaps the one to have described it most

beautifully (apart, one may certainly argue, from the Apostle Paul).

When Lewis writes

that “a young atheist cannot guard his faith too carefully,” it means something

entirely different than if I were to write the same thing, for with Lewis the

truth was borne out by experience. And yet, I very much might write something similar, for the truth is one that can,

indeed, observed: I have seen countless atheist individuals stumble over

themselves to avoid being exposed to Christian ideas, as if they were made of

poison gas, just as we have all seen atheist organizations pull out all stops

in order to stop the world from being exposed to the horrors of Christian

imagery. The attitude of atheism (and perhaps rightly so) has lately been one

of absolute quarantine—only by preventing any exposure to the beliefs and ideals

of Christians may one be made absolutely safe from them. The unwary atheist is

very apt to trip over a misplaced cross and suddenly be wracked by guilt over

his sin (I say this as if it were a joke, but in truth that is, often enough,

not far from the truth).

Well, the joke

is on them, because their attempts have never worked. The odd thing about

Christianity is that, the harder it is struggled against, the more powerful it

becomes, like a bacteria strengthened by penicillin. The Communists of the Soviet

Union understood this well enough to ban the Bible, though they failed to ban

Dostoyevski and Tolstoy, whose works are inseparable from their Christianity;

and Christianity thrived in Russia. Absolutely thrived.

The point of

this is that, in every way, it is the Christian who is free, while it is the

humanist who must guard himself with censorship. They may be called slaves of

God, but on earth they are the only ones who know freedom. Christians may read

what they like without fear of being exposed to the horrors of unbelief; they

may explore the truth in science while allowing for every possibility, while

the humanist is restricted to the tiny little box of unbelief (it is not God’s

fault that Christians often fail to understand this themselves).

Lewis, for

example, made the tragic mistake, while still an atheist, of reading Chesterton

(he was young and unprepared and did not guard his atheism as well as he,

perhaps, should have). “Then I read Chesterton’s Everlasting Man,” he writes, “and for the first time saw the whole

Christian outline of history set out in a form that seemed to me to make sense.

Somehow I contrived not to be too badly shaken. I already thought Chesterton

the most sensible man alive ‘apart from his Christianity.’ Now, I veritably believe,

I thought – I didn’t of course say; words

would have revealed the nonsense—that Christianity itself was very sensible

‘apart from its Christianity.’”

Reading Lewis—particularly

his allegorical novels and many of his essays—one can understand quickly what

he appreciated about Chesterton. It was the unique and astonishing tension (but

not contradiction) between the academic and the fantastic; between reason and

myth, history and poetry. It was a Christianity that could be reasonably

defended—logically, historically, scientifically—but at the same time a

Christianity that set itself as a fixture within the soul—the seat of myth and

fantasy. In Christianity, one has the freedom to look at Lewis’ Narnia books

and proclaim, without hesitation or qualification, that they ought to be seen

as works of non-fiction; that they might find a better home in the “History”

section of the library than in “Children’s Fiction”, for hidden within their

stories is a history of the world that carries far more truth than Gibbon

or Herodotus, and far deeper insight into true humanity than Kant or Descartes.

But

before he would ever come to write these books (and many others), Lewis struggled

mightily against the pull of Christianity; he felt, to use a phrase borrowed

from Francis Thompson’s poem, that he was being pursued relentlessly by the

Hound of Heaven.

Thompson

knew the struggle well:

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind; and in the mist of tears

I hid from Him, and under running laughter.

Up

vistaed hopes I sped;

And

shot, precipitated,

Adown Titanic glooms of chasmèd fears,

From those strong Feet that followed, followed after.

Lewis’s own story is, primarily, the

story of his flight and of his internal struggle; a fierce battle with the

truth that was welling up inside him. It is a strange thing, the atheist who is

compelled toward Christianity, for with every last gasp he will cry out that he

is only fighting to preserve truth, to preserve reason; that he is fighting, facts

against faith, when in actuality he knows (else he would not be fighting) that

they are fighting against truth

rather than for it (or there would be no struggle). Further, it is only by

faith that the atheist may to ignore the truth and remain an atheist—but only

the worst, blindest sort of faith, the sort that allows one to hold fast to

some ideal, even if a greater, truer ideal has presented itself. It is

something far different from the faith of the Christian.

Lewis’s own journey culminated, of

course, in his eventual conversion. Little by little the truth chipped away at

the walls of protection he had built up around himself, until at last they

crumbled. But it was not, as are so many superficial, temporary conversions of

today, a matter of a momentary decision, where one is stopped suddenly in their

tracks. Nor was it particularly dramatic. No, it was far too genuine for that.

“I was driven to Whipsnade one sunny morning,”

Lewis wrote of the first moments of his new life. “When we set out I did not

believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and when we reached the zoo I did.

Yet I had not exactly spent the journey in thought. Nor in great emotion.

‘Emotional’ is perhaps the last word we can apply to some of the most important

events. It was more like when a man, after long sleep, still lying motionless

in bed, becomes aware that he is now awake. And it was, like that moment on top

of the bus, ambiguous.”

It

is telling that Lewis should have titled his autobiography Surprised by Joy, for this is precisely the thing that can only be

understood by someone after discovering Christianity. It was, in part, an

intellectual understanding that began Lewis on his path to religion, and a

reasonable, sensible, logical sort of faith. He accepted its truth because he

realized that it was true; not, particularly, because of the good it would do

for him. Lewis would remark later that it is a grave mistake to become a

Christian believing that it will make life easier; one believes in Christ because

of His truth. That being said, what

Lewis discovered in Christianity, after the Hound of Heaven had caught up to

him after all, was that, despite the difficulties, despite the requirements,

despite being made into a servant of God, Christianity means true, lasting joy.

“I

call it joy,” he wrote, “which is here a technical term and must be sharply

distinguished from both Happiness and from Pleasure. Joy (in my sense) has

indeed one characteristic, and one only, in common with them; the fact that

anyone who has experienced it will want it again. Apart from that, and

considered only in its quality, it might almost equally well be called a

particular kind of unhappiness or grief. But then it is a kind we want. I doubt

whether anyone who has tasted it would ever, if both were in his power,

exchange it for all the pleasures in the world. But then Joy is never in our

power and pleasure often is.”

Lewis

knew well that what he found in Christ was the same that Thompson had foreseen

as he concluded his poem, as at last God catches up to the Prodigal and offers

him a word of comfort:

“All which I took from thee I did but take,

Not for thy harms,

But just that thou might'st seek it in My arms.

All which thy child's mistake

Fancies as lost, I have stored for thee at home :

Rise, clasp My hand, and come !”

Halts by me that footfall :

Is my gloom, after all,

Shade of His hand, outstretched caressingly?

“Ah, fondest, blindest, weakest,

I am He Whom thou seekest !

Thou dravest love from thee, who dravest me.”

The

fundamental appeal I have felt toward Lewis’s theology, which he espoused again

and again in form after form after coming to Christianity, is similar to that

which draw me toward Chesterton and Muggeridge, and that is its devotion toward

truths that are universal; ideas that might be capable, if taken seriously, to

unite Christendom at last. It wasn’t as if Lewis wasn’t himself part of a

particular sect of Christianity (he was a devout Anglican, much to the dismay

of his friend, J.R.R. Tolkien, who hoped that he would become a Catholic), but

as he wrote, he wrote of truths unquestionable. Whether in his apologetic works

(Mere Christianity stands almost

alone among 20th century explanations of God, while The Problem of Pain is a beautiful take

on a particularly vexing question), his allegorical stories (The Great Divorce, The Screwtape Letters,

Till We Have Faces) or his more straightforward theological works (Refletions on the Psalms, The Four Loves,

The Weight of Glory), the true beauty, the true joy, is that the truths are

primary. Lewis expresses the core principles of Christianity, without being

bogged down by sectarian nonsense.

(it

deserves note here that, as he grew in stature as a Christian writer, he

continued to hold a chair in Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge

University; it is fair to say that today’s universities would surely never

stand for such a conflict of interests)

The

root of Lewis’s mainstream popularity is due in part to his highly accessible

works—particularly The Chronicles of Narnia,

Mere Christianity and The Screwtape

Letters. Like Chesterton, however, it is not difficult to argue that at

least part of Lewis’s longevity may be attributed to the fact that the pages he

composed are filled—at times over-filled—with

perfectly composed phrases that almost seem made to be removed and used

elsewhere (some Lewisisms, such as, “Someday you will be old enough to start

reading fairy tales again,” sounds suspiciously like something Chesterton

himself would have said). It is almost as if one could tear apart his books,

sentence by sentence, and then put them back together in a different order,

without losing the heart of his ideas. He is, in short, endlessly

quotable—enough so that one is likely to forget that the many phrases for which

he is famous are perhaps even more powerful in their original contexts.

Words,

Lewis knew, carry the potential for power greater than any wizard’s wand or

witch’s cauldron if wielded rightly. God, after all, was in no way stingy when

he chose the languages of men as a means of revelation. It was no accident that

the scripture came down to us as a book. Words are often the weakness of men—they

have a way of finding their way into the soul—and Lewis, better than most,

wielded the weapon rightly; in part, because he had come to truly understand

the lostness of man and the stark disparity between the kingdoms of God and

man.

“Indeed,” he wrote in

one of the most enduring passages from The

Weight of Glory, “if we consider the unblushing promises of reward and the

staggering nature of the rewards promised in the Gospels, it would seem that

Our Lord finds our desires, not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about

with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an

ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot

imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too

easily pleased.”

No comments:

Post a Comment